The Golden Age — What it Was, and Why Art-Cased Pianos Matter

September 30, 2025 by Sophie

When collectors talk about the Golden Age of the piano they usually mean the nineteenth century into the early twentieth — roughly from the piano’s technical maturation (stronger frames, more reliable actions) through the years when wealthy households and public concert life both embraced grand and upright pianos. Pianos from this era are simultaneously musical instruments and decorative objects. These pianos were made to be seen and to be heard: their veneers, inlays, carvings and sculptural legs and lyres communicated status as clearly as their tone.

Europe at the 'fin de siècle' was a continent in which newly concentrated wealth, accelerating industrial production, and expanding international markets reshaped cultural life. The effects were immediate and visible. Rapid industrialization and urban growth created a large, prosperous middle-class with disposable income and a taste for cultural consumption. Manufacturers and merchants funnelled that purchasing desire into goods and experiences that signalled status and modernity, from pianos and parlour furniture to exhibition catalogs and framed canvases.

"These pianos were made to be seen and to be heard: their veneers, inlays, carvings and sculptural legs communicated status as clearly as their tone"

Bespoke Elegance: Pianos as Extensions of Interior Design Trends

For Europe’s wealthy households at the end of the 19th century, the piano wasn't merely an instrument — it was a centrepiece, often commissioned with bespoke cases to harmonize with the broader decorative scheme of the interior. Aristocratic salons and middle class parlours incorporated pianos to demonstrate taste, matching their veneers, carvings, and inlays to prevailing art and design styles. During the mid-Victorian decades, interiors often embraced eclectic historicism, borrowing Gothic, Renaissance, or Rococo motifs; by the late 19th century, the Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau introduced sinuous lines, stylised florals, and a focus on craftsmanship as art. In more conservative homes, Neoclassical references — symmetry, columns, palmettes — remained fashionable, while by the early 20th century, forward-looking households began incorporating Jugendstil or early Art Deco elements. A grand piano with Empire-style gilt mounts, Rococo scrollwork, or Art Nouveau marquetry thus served as both a musical instrument and a declaration of cultural alignment with the decorative trends of the day, ensuring its resonance visually as well as sonically.

Social history: salons, gender, class and domestic culture

Why did the piano spread from aristocratic courts into middle-class homes?

Several overlapping developments explain the piano’s shift from an emblem of royal privilege to a fixture of middle-class domestic life

Industrialization

- Advances in manufacturing, transport, and large-scale production techniques lowered costs and improved availability. What had once been the preserve of courts and noble estates gradually became attainable for prosperous merchants, professionals, and the growing middle classes. The piano evolved from an elite status symbol into a common marker of respectability and upward mobility.

Salon and Parlor Culture

- The social practices of culture changed in ways that reinforced commercial expansion.

By the mid-19th century, the piano had become the focal point of home entertainment and sociability. Musical evenings, intimate gatherings, and salon performances relied on it to provide both atmosphere and cultural cachet. Seasonal subscriptions to concert series, and membership in art societies were both social rites and consumer choices. Owning and playing the piano communicated refinement, education, and moral standing. For young women in particular, the instrument offered a socially acceptable avenue for musical accomplishment and public demonstration of taste, shaping a repertoire of salon pieces, character works, and simplified adaptations suited to amateur performers.

Gender and Domestic Economies

- The piano also carried significant social weight in defining gender roles. Women were often expected to be proficient at the keyboard as part of their cultural education, yet the instrument also opened pathways to professional activity as teachers, composers of parlor music, or salon hostesses. The instructional materials and musical styles developed for these contexts left a long legacy, influencing piano pedagogy and beginner repertoire well into the modern era.

International currents — migration, trade, and diplomatic taste

Piano-making and piano taste were transnational phenomena. German craftsmen migrated to the U.S. (the Steinweg/Steinway family is the classic example), Austrian and Czech makers fed Vienna’s concert culture.

World’s fairs, industrial exhibitions and international salons linked European makers with buyers worldwide. These events functioned as spectacular marketplaces and informed trends: they broadcast new materials, motifs and manufacturing techniques to millions of visitors, promoted cross-border trade in luxury and manufactured goods, and legitimized avant-garde design while also creating mass appetite for decorative objects that could be placed in a home.

The result was global cross-pollination: Viennese tonal ideals, German mechanistic precision, and later American manufacturing scale all mixed in international markets.

Technical Maturation of the Instrument

Each technological advance changed what composers and pianists could do: the richer, more sustained sonorities supported Liszt’s virtuosic experiments; improvements in touch and dynamic range allowed subtler Impressionist colors; mass production of uprights expanded amateur repertoire and pedagogy. In short, the instrument’s evolution shaped the music that became canonical — and the music, in turn, shaped the instruments makers prioritized. If you visit a Golden Age showpiece, listen as well as look: a nineteenth-century Bechstein will speak differently from a later Steinway, and those differences are musical history encoded in its construction.

Living examples from Besbrode Pianos Golden Age of Pianos Collection

1. King Edward VII Blüthner Grand Piano ( 1899 )

Maker and Provenance

Maker

Blüthner, Leipzig, Germany — one of the major piano makers during the late 19th century, known for warm tone, innovation (e.g. aliquot stringing), and fine cabinetry.

Provenance:

Originally purchased by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra; placed in the ballroom of Marlborough House. Also exhibited at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle.

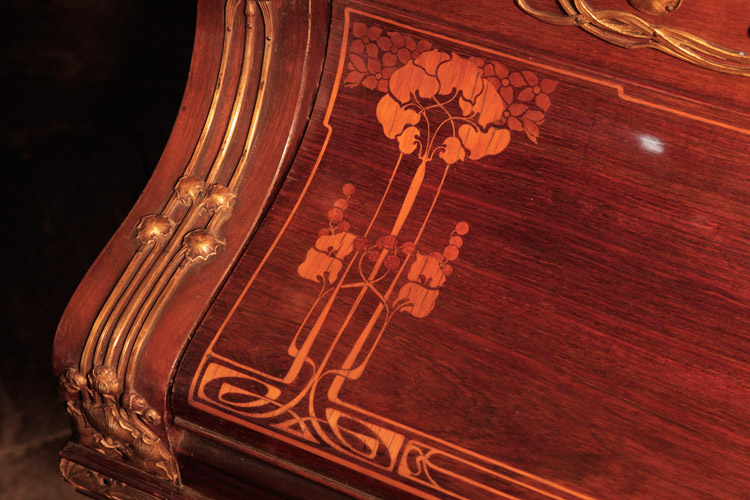

Stylistic & Decorative Notes

The case exhibits Art Nouveau design elements: stylised foliage, whiplash lines, female heads with flowing hair; also Empire-style gilt mounts with palmettes, stars, and whimsical detail. The fine marquetry uses a variety of coloured woods. The music desk is a standout feature in bevelled glass with intricate metal filigree. Large sculptural legs are carved with sunflower and foliage motifs with gilt mounts.

The ultimate blend of high-craft decoration and functionality reflects its dual purpose, both as concert/salon instrument and showpiece.

Why It Matters

Intersection of Art & Power:

Acquired by royalty, exhibited at a World’s Fair (1900 Paris), and placed in a major royal residence. It is a symbol of prestige and cultural power through decorative arts. It reflects how monarchies and elites used the piano for display in salons and courts, not just as musical tool.

Art Nouveau in Furniture / Decorative Arts:

The piano is a vivid example of how the Art Nouveau movement (roughly 1890-1910) penetrated not just painting or architecture, but also cabinetmaking. The whiplash curves, stylized natural motifs, emphasis on flowing line, and high craftsmanship are typical of the period’s ethos. Thus it stands at the intersection of musical and visual culture at the turn of the 20th century.

Technical & Acoustic Value:

A Blüthner grand, rich and mellow in the mid and treble with warmth in bass and a responsive action suited to the repertoire of the late Romantic period. This is a preserved piece with few previous owners.

Cultural Memory & Collectibility:

Because of its royal connections, its appearance in an international exhibition and its exquisite artistry, this instrument is rare and highly collectible. It helps define what luxury meant for musical instruments prior to modern mass production and standardization. It also reminds us of a fading skill set: the cabinetmaking, the inlay, the subtle ornament, which today are hard to find.

Read more about this King Edward VII Blüthner Grand Piano

2. Richard Strauss Ibach Model 2 Grand Piano ( 1907 )

Maker and Provenance

Maker

Ibach, Germany — a prestigious maker founded in Barmen in 1794, known for quality, especially in Germany, often supplying domestic and salon instruments, sometimes concert instruments.

Provenance:

This is one of two of this design offered to the composer Richard Strauss. Serial number 56278. Designed by Emanuel von Seidl for Strauss. Two pianos were made almost identical in this design except, the other #56279 had low, square piano cheeks. Richard Strauss chose that one as he intended the piano for his home where he hosted concerts and wanted his audience to be able to see his hands. This piano remained in the posession of Ibach and was used in exhibitions for promotional purposes.

Stylistic & Decorative Notes

The case is cherry wood in a checkerboard pattern with contrasting dark squares on the lid. The music desk is openwork criss-cross. The gate legs have four contrasting black spindles. The design is much more restrained than super-ornate art case pianos; it leans toward refined geometry rather than exuberant ornamentation. The minimal lines and flat planes lacking carvings or embellishment were forward thinking and prescient of the modern style to come.

Designed by Emanuel von Seidl, an architect / interior designer, whose style reflects the move towards less superfluous decoration and more harmony of form, in line with changing tastes in the early 20th century.

Why It Matters

Composer & Performance Context:

That this was offered to Richard Strauss ties the instrument directly to a leading figure of modern orchestral and operatic music. The choices in design reflect his understanding of performance, aesthetics, and visibility.

Shifting Taste:

This Strauss Ibach demonstrates a shift in taste toward clarity, restraint, visibility of form and function. As the decorative excess of the 19th century receded, designers were experimenting with geometry, pattern, and simpler materials. This piano showcases the introduction of a modern style in interior design, architecture, and music in early 20th century.

Technical Survival & Restoration:

This instrument has been sympathetically restored. Thus it gives modern players direct experience of pre-WWI instrument engineering: string scale, action weight, touch, tone.

Cultural Bridge:

This piano is a bridge between Romantic and modern eras: musically composers were pushing boundaries (Strauss himself), socially Europe was going through urbanization, new design movements, political tension; instruments like this are artifacts of that transition.

Read more about this Richard Strauss Ibach Model 2 Grand Piano

3. Steinway Centennial Concert Grand Piano ( 1874 )

Maker and Provenance

Maker

Steinway & Sons (New York). One of the most influential piano makers globally, combining innovations (cast iron frame; over-stringing; duplex scaling etc.), strong export networks, and high prestige.

Provenance:

These pianos were tied to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition; the term “Centennial Grand” comes from that context. Steinway entered examples in that exhibition; the model gained acclaim. Similar examples are still preserved. This model is the direct predecessor to the now flagship Model D.

Stylistic & Decorative Notes

The case is Rococo style: ornate carving, scrolling acanthus leaves, arabesque filigree, lavish high relief carving especially on legs, lyre and cabinet border.

Material is rich rosewood. The instrument design reflects Steinway’s innovations of the period: an early amalgamation of over-stringing and high tension, strong frame to support more strings, with greater dynamic range.

Why It Matters

Piano Technology & Modern Concert Grand Origins:

The Centennial Concert Grand is one of the first Steinway instruments that approached what we think of as the modern concert grand: full length, powerful projection, broader dynamic range, sustained tone. It was designed in response to demands for large-scale concert halls and virtuoso repertoire.

Exhibition & International Recognition:

The Centennial was tied to big world exhibitions (like the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial) — venues where piano makers competed not just on tone but on craftsmanship, decoration, and prestige. By winning or gaining medals, Steinway raised its brand internationally. The ornamental Centennial Grands are considered showpieces.

Art of Cabinetmaking:

The Rococo style of this instrument is extra-ornate, showing how, even into the late 19th century, historical revivals and decorative trends from earlier centuries were still strong influences in furniture and instrument design. It tells us about taste: for theatricality, ornament, opulence.

Legacy for Collectors:

For pianists and restorers today, these Centennial Grands are precious because they embody earlier Steinway action designs that differ from later mass-produced models. For collectors, their rarity, ornament, condition and provenance make them sought after.

Read more about this Steinway Centennial Grand Piano

Final note — why this history still sings

The Golden Age of pianos is fascinating because engineering, commerce, decorative arts, gender studies, and global politics all leave fingerprints on surviving instruments. Looking at an art-cased piano is like reading a small social history — who had money, what they wanted to show, which nations traded with whom, and what music was fashionable. The instruments from this Golden Age give us tactile access to those conversations between makers and society.

View Besbrode Piano's Golden Age of Pianos Collection